Thoughts on Internet distraction, pt. 2

By Jacob Siefring

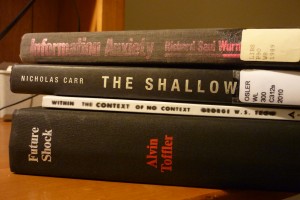

If you descend from the Mont Royal hillside on which the McGill School of Information Studies building is situated and traipse through central campus to arrive at the Schulich Engineering library and go into the stacks at QA 76.9 C 66, you’ll be looking at a strange welter of sensational and dystopic-sounding titles of books. These titles include:

Trapped in the Net; Life on the Screen; The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace; Silicon Shock; The Net Effect: Romanticism, Capitalism, and the Internet; Technobabble; Digital Diaspora; Cyburbia; Slaves of the Machine; Moths to the Flame; High Noon on the Electronic Frontier; Monster or Messiah?; Digerati; War of the Worlds.

Before this smatter of classificatory wonder I found myself, having come in search of Theodore Roszak’s The Cult of Information: A Neo-Liddite Treatise on High-Tech, Artificial Intelligence, and the True Art of Thinking, first published in 1986 and later revised. The book is, of course, hopelessly outdated technology-wise but nevertheless an impassioned, thoughtful, and even touching defense of humanistic values (the ‘art of thinking’).

One passage in it I found absolutely critical, and a complement to all of the points raised by The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. Here’s Roszak:

Introducing students to the computer at an early age, creating the impression that their little exercises in programming and game playing are somehow giving them control over a powerful technology, can be a treacherous deception. It is not teaching them to think in some scientifically sound way; it is persuading them to acquiesce. It is accustoming them to the presence of computers in every walk of life, and thus making them dependent on the machine’s supposed necessity and superiority. Under these circumstances, the best approach to computer literacy might be to stress the limitations and abuses of the machine, showing the students how little they need it to develop their autonomous powers of thought. (242)

The last line in bold rings truest. Given that technology is “limited” and prone to “abuse”–read, overuse–parents and educators need to be responsive to this potential.

As a parent of a three-year-old, I confess that I’m terrified of the technological “gray” territory that lies ahead. How will my partner and I define and fix boundaries? Such as: At what times is it appropriate (and not appropriate) to use an electronic device? At what age should my daughters first acquire wireless electronic devices? Six? Five? Eight? Seven? How closely will my partner and I have to police our daughters’ use of their devices–for what activities? What would a ‘reasonable’ time allocation look like for such activities as gaming, texting, and video streaming? In brief, I feel as though I were staring off a cliff into a fog, or peeking into the box of some Pandora as yet unseen.

After calling for children to be educated for an awareness of the limitations and abuses of computing power, Roszak cites Sherry Turkle’s book, Life on the Screen (1995), and speaks of the importance for children of experiencing nature and observing the behavior of wild animals. This almost strangely feels like a non sequitur, but I don’t think it is. Unless we situate our understanding of technology relative to the continuum of human experience, we risk failing to grasp what its proper use might be.

As for classification tier QA 76.9 C 66: that’s in the section of the Library of Congress classification outline (QA 75.5 – 76.95) defined by the parameter “Electronic computers. Computer science.” I would add that we’re looking at something like Computers, their (dystopic) effects on individuals and on society. It’s a remarkable grouping of books and ultra-relevant for our time; that much is certain. Such recent titles as discovered iDisorder: Understanding Our Obsession with Technology and Overcoming Its Hold on Us (Larry Rosen, 2012), Digital Diet: The 4-step plan to break your tech addiction and regain balance in your life (Daniel Seeberg, 2011), and Cyber Junkies: Escape the Gaming and Internet Trap (Kevin Roberts, 2010) indicate the rising visibility of our problematic relationship to our computing technologies. (Sieberg’s book I actually read, after finding it in the ‘new books’ section of the Atwater Library and Computing Centre, where I volunteer. It contains some sage advice you might find helpful if you want to curtail your electronic attachment. Through it I learned about RescueTime, a tool that provides weekly analytic reports on your online behavior.)

Final note: This blog is currently seeking submissions from any student, current or former, of McGill’s School of Information Studies. Tell your peers about your summer job/practicum/internship; reflect on the degree you just completed; rant about how hard it is to find a job; or tell us what you’re reading that’s good (or bad). Direct commentaries to jacob.siefring@mail.mcgill.ca. Here at Beyond the Shelf I will not be very active, but will occasionally do some cross-posts from my blog, bibliomanic, where I will be posting regularly.