Thoughts on Internet Distraction

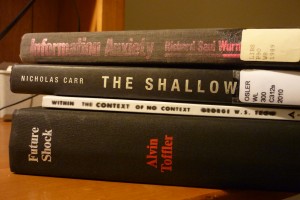

In June, 2010, W.W. Norton published The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, by Nicholas Carr. Because I frequently read book reviews, I was aware of and interested in this book for some time before I got around to it. What gave me a sense of urgency to read it was seeing Jonathan Safran Foer’s high praise of Carr’s work. He basically called it the book of the year. The book develops ideas advanced in Carr’s article, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”, published in The Atlantic (Jul-Aug. 2008). Before that, Carr published two books on technology, notably Does IT Matter? Information Technology and the Corrosion of Competitive Advantage and The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, From Edison to Google. He’s a former executive editor for the Harvard Business Review.

Carr believes — and shows, using lots of evidence drawn from research in neuroscience and cognitive science (the book is shelved in McGill’s Osler medical library) — that our interlinked computing technologies pose a serious challenge to deep thought, hampering our capacity to reflect and contemplate in meaningful ways. This isn’t exactly a groundbreaking claim; at least, not for anyone who has had the experience of, while piloting a web browser, being unable to focus for any length of time on the task at hand, or who has found their attention increasingly diverted and distributed through a web of hyperlinks. Figures of speech to describe our computerized, information-saturated mental state abound: popcorn brain, mental obesity are among the most apt. Forget information overload.

I think we’ve most all of us felt an inkling of suspicion that web use might influence thought patterns and micro-behavior. Why Carr’s book is important is because it culls together enough scientific research, present-day information, and historical context to show us that — beyond the shadow of a doubt — the net is rewiring our neural circuitry and impairing our intelligence (that is, at least insofar as high-level intelligence used to mean the ability to grapple with and dissect complex problems, as well as to remember lots of information). If you’re skeptical of this claim, I encourage you to read Carr’s book. Nevertheless, for the hurried, here are a few of what I retain as its most salient points.

- Developers of automation-technologies and decision support systems are often motivated by the desire to relieve ordinary people of the burden of executing routine, mundane tasks. They want to make life easier for everyone; so, they advocate outsourcing decision-making to computers and the writing of algorithms to assist in search retrieval (namely, Google’s PageRank). These evangelists of technology often share the view of Wired writer Clive Thompson, who refers to the Net as an “ ‘outboard brain’ that is taking over the role previously played by inner memory. […] He suggests ‘by offloading data [from our brains] onto silicon, we free our own gray matter for more germanely “human” tasks like brainstorming and daydreaming’ ” (Carr 180). But this conception of the brain, and the well-intentioned idea that technology will allow our thoughts to become more serene and lofty, are dead wrong, Carr shows. Unlike a computer, the human brain does not have a limited storage capacity; experts on memory affirm that “the normal human brain never reaches a point at which experiences can no longer be committed to memory; the brain cannot be full.” “The amount of information that can be stored in long-term memory is virtually boundless” (192).

- We tend to forget that our interaction with technology is always bidirectional, not just unidirectional. Human intentions may determine behavior, but, as Carr reminds us, tools and media exert a powerful shaping force on consciousness and behavior — especially once they become dominant or integrated into daily routines. This is well summed up in John Culkin’s formulation, “We shape our tools, and thereafter they shape us.” And every tool, every medium has its specific limitations — from the map, to the typewriter, to the power loom, to the clock, as Carr shows (209-211). The searchable internet’s limitations include its isolation of facts and information from their various contexts; and the sprawling, heterogeneous character of the information that’s found there. But enough.

For Carr’s critics, his points are bitter pills to swallow, and many have dismissed them outright. His argument has been called “defeatist” and “reductionist.” From my personal experience, I tend to agree with Carr. The internet has changed the way we think, and, for the most part, not for the better. But at least there’s good news. Exposure to Carr’s book has made me more self-aware of my overuse of the internet and of its insidious effects on my thought patterns. Since having read The Shallows, I’m less inclined to take a laptop with me now when I go out. Even as I write this, I have used the internet-restrictive application Freedom (available for a free five-use trial period!) to curb my forays into the hyperlink jungle, where my thought wanders away and my will atrophies. I think I can even hear myself think. Can you? Hear me? Hear yourself think? Not get distracted?